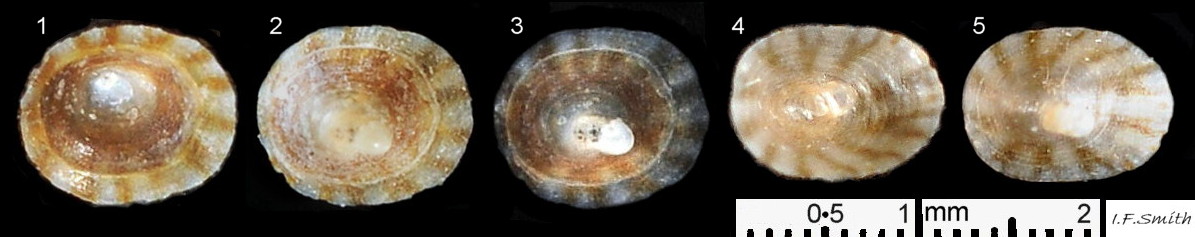

Juvenile T. virginea from shell-grit samples. White semi-spiral protoconch attached to apex.

1 & 4: interiors lack pigment; translucency reveals exterior markings which are usually brownish at this stage, and cause frequent misidentification as T. testudinalis.

3: in water so more translucent than other dry specimens.

APPENDIX re range advance/retreat BELOW

marinvert.senckenberg.science/image-browse/

The Distribution Limits of Testudinalia testudinalis.

Appendix for full species account at flic.kr/s/aHskbm8fpS

Ian F. Smith October 2020

This appendix will be amended if new evidence requires it.

The following is based on available specimens and images, and on information from workers with many years of experience of T. testudinalis. Over fifty museum curators, academics, professionals, amateur shore workers and divers have provided information, and appeals have been made for images or specimens to online groups of shore workers and divers with a total membership of over a thousand.

Information from regions with the most complete historic and current evidence suggest that the species extended its range southwards in the relatively cold 19th century and has receded towards its previous range in the climatic warming of the late 20th and early 21st centuries A11 A11 Appendix to T. testudinalis account. Historic and recent, southern limits of distribution. . The range expansion is demonstrated with the date of the earliest recorded appearance of T. testudinalis at different latitudes. Early recorders were a limited number of specialists, and their accuracy can be checked from museum specimens and their published descriptions and images.

Recording its disappearance from localities has many problems as absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The onus of proof, by display of specimen or image, rests on those who maintain it is still present at a locality. To assess the probability of decline, reliance has been placed on those with the necessary identification skills who have frequently investigated an area over a period of years. If numbers were noted to decline, followed by no finds while consciously watching for it for several years, it is reasonable to think that the species is lost or at undetectably low numbers. Occasionally, such assumptions are reversed by subsequent finds, such as happened in the Isle of Man.

Readers are asked to contact the author with any visual evidence that affects the findings below, so that the Flickr version of this account can be adjusted accordingly.

A particular problem with documenting the recent decline northwards of T. testudinalis has been the very frequent mistaken recording of T. virginea as it. This has several probable causes:

1) Specimens of T. virginea can be mistaken for it if the exterior markings are concealed by epizooic growths A1 flic.kr/p/2jW2ChD or are worn away A5 flic.kr/p/2jW2C7i .

2) The markings on early juvenile T. virginea, such as tiny specimens from shell-grit samples, are often brownish and mistaken for those of Testudinalia testudinalis A1 flic.kr/p/2jW2ChD & A2 flic.kr/p/2jW74ig .

3) The vernacular name of T. testudinalis, “Common tortoiseshell limpet”, has lead many recorders to think it is the tortoiseshell limpet that is found commonly in England and southern Ireland where it is absent or extremely rare. It is T. virginea, the “White tortoiseshell limpet”, that is common there and frequently misidentified. To reduce this confusion, the vernacular name of T. testudinalis was changed to the “Northern tortoiseshell limpet” in October 2020 on the UK Species Inventory controlled by the Natural History Museum, London. This problem does not apply in America where T. virginea does not occur and the vernacular used for T. testudinalis is simply “Tortoiseshell limpet”.

4) Distribution maps, such as NBN Atlas, show historic and recent records with the same symbol, so users may think their finds in areas where it is lost are plausible because of the historic records shown.

5) Recent misidentifications added to the T. testudinalis map on NBN Atlas, by amateurs, professionals and academics alike, further add to the apparent plausibility of records in areas where it has gone. Sophia Ratcliffe of NBN is making efforts to have them recognised and removed, but the cooperation of some data providers is difficult to obtain.

6) The multiplication of fauna recording organizations, online interest groups and ways of submitting records online has drawn in many enthusiastic but non-specialist contributors. Many are averse to disturbing specimens for close examination and rely on un-posed photographs for identification.

Regional Detail.

North-east England has the most detailed data. It is assumed that similar climate changes to those described occurred in other areas.

British North Sea

Forbes (Forbes & Hanley, 1849) knew of T. testudinalis at many places in Scotland but not in England. He predicted the range expansion southwards which reached the Farne Islands by 1856, Roker by 1857 (Tate, 1863 in Foster-Smith, 2000); Hesleden by 1861 (Dove Marine Laboratory manuscript, 1862, in Foster-Smith, 2000); Hartlepool by 1863 (Hancock, 1863, in Foster-Smith, 2000); Sandsend by 1901 (Lebour, 1902); and Flamborough before 1910 (Hargreaves, 1910) A3 flic.kr/p/2jW74hp & A4 flic.kr/p/2jW6fb9 . This advance south of over 220 km took place in the cold period c. 1855 – c.1920 when the ten year running mean temperature in central England was always below the mean temperature of 1961 – 1990 A4 flic.kr/p/2jW6fb9 . From c.1920 to the late 1980s the ten year running mean temperature rose to fluctuate around the level of the 1961- 1990 mean. In this period, records of T. testudinalis continued to be made so it seems to have maintained its expanded range, though no specimens or images have been seen, so some may be misidentified T. virginea . From the late 1980s to 2019 the ten year running mean temperature has risen to unprecedented heights well above the 1961-1990 mean and there has been a marked reduction of reliable records of T. testudinalis. Sue Hull, Programme Director Marine Biology, University of Hull, observed occasional rare specimens in Yorkshire from 2002 to 2007 with a final single specimen at Ravenscar in 2010. Paula Lightfoot, who did extensive shore work and diving in Yorkshire and the North East of England from 2010 to 2020, saw none despite consciously looking for it. The experience of a large number of other shore workers and divers conforms to that of SH and PL.

NBN Atlas had several recent records of it in the North East, but all photos shown were of misidentified T. virginea , and all 2010 to 2020 records were retracted by those who recorded them, though some may remain on NBN Atlas until the Data Providers allow NBN to remove them. The distribution limit may have fallen back to its pre 1856 position in south-east Scotland. The furthest south in the British North Sea, recent (2020), live-taken image seen by IFS is from Edinburgh, 56.00° N A5 flic.kr/p/2jW2C7i . It may yet survive further south in Scotland and the extreme north of England as there is a live-taken specimen in National Museums Scotland from Eyemouth 55.88° N (1981). Re-examination of 1980s sites is desirable to see how far south beyond Edinburgh it still occurs live.

Other records for 2010 to present in NE England should not be relied on unless evidence can be shown, and users of NBN Atlas should be aware that the T. testudinalis map shows historic records in North East England at sites where it no longer occurs.

West coast of Ireland

No historic data available. Furthest south recent record at Mulroy Bay, N. Donegal 55.15° N, 07.68°W. (J. Nunn pers. comm. July 2020).

East coast of Ireland

The spread south is mentioned in Forbes and Hanley (1849) thus: “On the Irish shores it has found its way as far south as Dublin Bay, in which well-searched district it has been noticed only of late years ; it is there ‘abundant, near Williamstown, on stones above low water-mark’ (Hassall)”

The furthest south historic (pre 1893) record is at Bray, Wicklow, 53.20° N. The specimen is in the National Museum of Ireland and has been examined and catalogued (Nunn & Holmes, 1995).

There are several recent records of T. testudinalis from Carlingford Lough, about 95 km north of Bray, such as at Greencastle, 54.04° N (2013, det. J. Nunn) and many further north A6 flic.kr/p/2jW2C3R . No recent, reliable records further south have come to light in this inquiry.

Isle of Man

The spread south of T. testudinalis to the Isle of Man, probably from Northern Ireland or southern Scotland, is mentioned in Forbes and Hanley (1849) thus: “appeared since 1836, and multiplied considerably on the north coast”. Subsequent records in Moore (1937) include Ramsey 54.32°N, (1878); Ballaugh 54.31°N, (1901); Fleshwick Bay 54.11°N, common, (1932); Port Erin 54.09°N, few, (1932).

A decline and apparent ‘loss of species from south of Isle of Man’ was observed when none was found in the years 2000 – 2005 where it had previously been found intertidally in the1970s and early 1980s (Hawkins in Mieszkowska, 2005), but it was present in 2017, at least sublittorally.

Furthest south, recent, sublittoral records at southern tip of island, 54.05° N (2014) and Niarbyl, 54.16° N (2017) A6 flic.kr/p/2jW2C3R .

North East Irish Sea.

The furthest south, historic record (pre 1910) is from Fleetwood, Lancashire 53.92°N A7 flic.kr/p/2jW2BXA . No information has been found on when, and if, it spread south from Scotland in mid 19th Century.

The furthest south post 2000 records with images are on the south coast of Scotland from Ardwell, Mull of Galloway, 54.77° N (2019) eastwards to Islands of Fleet, 54.81°N, 4.94° W (2017) A7 flic.kr/p/2jW2BXA . It was present in low numbers in1991 at Parton Bay, Cumbria 54.55° N. (S.J. Hawkins on NBN Atlas).

Wales

No image or specimen evidence has been found for T. testudinalis living in Wales recently or historically. The National Museum Wales has specimens of the species, but none is from Wales. A few publications such as Graham (1988) mention Anglesey without further detail. A specimen is rumoured to exist in the Zoology Museum, Bangor University, but the Collections Officer, Helen Gwerfyl, has been unable to find a specimen or documentation to support this. Appeals for images of T. testudinalis to sub aqua divers and shore workers in online groups with membership around 1000 have produced several images from Scotland, but none from Wales. There are several records in Wales on NBN Atlas, but none can be substantiated with specimen or image. All images viewed from all sources offered as T. testudinalis from Wales were of misidentified T. virginea .

Forbes and Hanley (1849) mention the possible source of reports of it from Wales thus:

“The locality ‘Bangor’, assigned to it by Mr. Sowerby, refers not to Bangor in North Wales, but to a place of the same name in the north of Ireland.”

Until specimens or images can be found to substantiate the presence of T. testudinalis in Wales, recently or historically, it should not be accepted as a confirmed resident. Any new records should be supported with specimens or clear images, preferably including the interior of a fresh shell.

South-west England

No historic records of T. testudinalis were made in this region in the period of its greatest extent 1855-1920, apart from a misidentification of T. virginea in Cornwall mentioned in Jeffreys (1865). It is most surprising that there are thirty records on NBN Atlas for the northern, cold water species, T. testudinalis, in this most southern, warm water area in the period of climate warming 1981 – 2013 when it was retreating northwards elsewhere. The data holders for most of the records are JNCC or Natural England. Records here were challenged as probable misidentifications of T. virginea in Wilkinson (2010) who reported, “JNCC are currently looking into the sources of these more carefully”, but no action has been taken in the ten years since. Unless evidence in the form of specimens or images can be produced, records of T. testudinalis in this area should be disregarded.

Continental coast of Europe

T. testudinalis occurs in Norway and south-west Sweden extending, both recently and historically, into the Kattegat and Öresund to the vicinity of Lund at 55.8° N where the limit of distribution is probably controlled by low salinity further into the Baltic A8 flic.kr/p/2jW73Zf .

T. testudinalis also lives on the Danish side of the Kattegat and Lillebaelt A9 flic.kr/p/2jW6ePC & A11 A11 Appendix to T. testudinalis account. Historic and recent, southern limits of distribution. to the outer fringe of the Kieler Bucht and Fehmarnbelt between Germany and the Danish island of Lolland where low salinity probably limits extension further east; this was also the historic limit stated in Meyer & Möbius (1872).

On the North Sea coast of continental Europe, no live-taken specimen or image further south than Norway and Sweden has been traced, but a dead, strandline specimen (date and location when live uncertain) was found at Lister Haken, Sylt, Germany at 55.04° N in 1969 A9 flic.kr/p/2jW6ePC .

Offshore there is an unlocalized mention of “central North Sea” (Götting, 2008) and an imprecise reference to “North Sea-Helgoland + deep channel + stony ground” (Zettler et al., 2018) but K. Janke, a biologist who worked many years on Helgoland, never found it there (pers. comm. V. Wiese).

East coast of North America

The furthest south historic (1914) record of T. testudinalis was at Hempstead Bay, Long Island, New York, 40.6° N A10 A10 Appendix to T. testudinalis account. Historic and recent specimens from North America. . The furthest south recent (2009) record on iNaturalist is East Matunuck, Rhode Island, 41.38° N , about 200 km north-east of Hempstead Bay A10 A10 Appendix to T. testudinalis account. Historic and recent specimens from North America. & A11 A11 Appendix to T. testudinalis account. Historic and recent, southern limits of distribution. . American records have extended more than 10° of latitude further south than in Europe probably because of the cold Labrador current extending south down the coast to the vicinity of Cape Cod.

In the St Lawrence River, the furthest upstream record on iNaturalist in the St Lawrence Estuary is at L’Isle-aux-Coudres (2020), 47.40° N, 70.34° W (dead, but unlikely to have been carried upstream against the flow). Furthest upstream live image on iNaturalist is Rivière-du-Loup (2018), 47.84° N, 69.54° W. The limiting factor is low salinity, so there has probably been little historic variation there with climate change.

Northern limits of distribution

Several museums hold specimens of T. testudinalis from the northernmost coasts of the land masses encircling the Arctic Ocean, including those which are icebound for part of the year. Although the southern limit of distribution is receding northwards, there seems little, if any, unoccupied coast for it to advance onto northwards with global warming. It might already extend undetected below the sea ice to the North Pole. Some most northerly museum-records on GBIF are:

North Alaska 71.3° N (1900); Devon Island, Canada 76.6° N (1962); northern Greenland 76.2° N (1894); north-west Iceland 65.88° N (2019) A12 A12 Appendix to T. testudinalis account. Specimen from north-west Iceland 65.88° N (2019) © S. Case. ; Svalbard 77.7° N (undated); Nenets Region, northern Russia 69.8° N (1875).

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank the following for information, images or specimens that helped establish the probable limits of T. testudinalis historically and recently. It is not intended to imply that all agree entirely with my interpretation of the available evidence.

Lin Baldock, Charlotte Bolton, Sarah Bowen, Paul Brazier, Blaise Bullimore, Shaun Case, Jon Chamberlain, Jane Delany, Jonas Ekstrom, Mike Elliott, Helen Gwerfyl, Steve Hawkins, Rosemary Hill, Anna Holmes, Rohan Holt, Sue Hull, Angus Jackson, Stuart Jenkins, Nia Jones, Paul Kay, David Kipling, Kerry Lewis, Paula Lightfoot, Kate Lock, Jim Logan, Aisling May, Krysia Mazik, Jim Middleton, Nova Mieszkowska, David Mozzoni, Will Musk, Naoise Nolan, David Notton, Claude Nozeres, Julia Nunn, Graham Oliver, Gustav Paulay, Anna Persson, Bernard Picton, Sankurie Pye, Poul Rasmussen, Sophia Ratcliffe, Allan Rowat, Ben Rowson, Julia Sigwart, John Slapcinsky, Sabine Stohr, Simon Taylor, Anders Telenius, Dawn Thomas, Ann Wake, Dawn Watson, Richie West, Vollrath Wiese, Andrew Wright and Richard Yorke.

References

Forbes, E. & Hanley S. 1849-53. A history of the British mollusca and their shells. vol. 2 (1849), London, van Voorst. (as ‘Acmaea testudinalis’) archive.org/stream/historyofbritish02forb#page/434/mode/2up

Foster-Smith, J. 2000. The marine flora and flora of the Cullercoats district. Newcastle upon Tyne University.

GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). Distribution map for T. testudinalis accessed October 2020. Includes many obvious errors such as far-inland or tropical locations. www.gbif.org/species/4369953

Götting, K.-J. 2008: Mollusca II. Meeres-Gehäuseschnecken Deutschlands. Bestimmungsschlüssel, Lebensweise, Verbreitung. Hackenheim, Conch Books.

Graham, A. 1988. Molluscs: prosobranch and pyramidellid gastropods. Synopses of the British Fauna (New Series) no.2 (Second edition). Leiden, E.J.Brill/Dr. W. Backhuys. 662 pages.

Hargreaves, J. A. 1910. The marine mollusca of the Yorkshire coast and the Dogger Bank.

J. Conch., Lond. 13: 80 – 105.

iNaturalist, Taxa information and map, Testudinalia testudinalis, accessed October 2020. www.inaturalist.org/taxa/415169-Testudinalia-testudinalis

Jeffreys, J.G. 1862-69. British conchology. vol. 3 (1865). London, van Voorst. (As Tectura testudinalis; archive.org/stream/britishconcholog03jeff#page/246/mode/2up .

Lebour, M.V. 1902. Marine mollusca of Sandsend. Naturalist, Hull.

Meyer, H. A. & Möbius, K. 1872. Fauna der Kieler Bucht, vol 2. Leipzig, Engelmann. p 7-9. www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/110011#page/4/mode/1up

Mieszkowska, N., Leaper, R., Moore, P., Kendall, M.A., Burrows, M.T, Lear, D., Poloczanska, E., Hiscock, K., Moschella, P.S., Thompson,R.C., Herbert, R.J., Laffoley, D., Baxter, J., Southward, A.J., & Hawkins, S.J. 2005. Assessing and predicting the influence of climatic change using eulittoral rocky shore biota. M.B.A. Occasional publication 20: p 26. www.researchgate.net/publication/281164392_Assessing_and_…

NBN Atlas species.nbnatlas.org/species/NHMSYS0021056387#tab_mapView

Nunn, J.D. and Holmes, J.M.C. 1995. A catalogue of the Irish and British marine Mollusca

in the collections of the National Museum of Ireland ~ Natural History, 1835-2008. Ulster Museum (Belfast) and the National Museum of Ireland (Dublin).

www.habitas.org.uk/nmi_catalogue/searchresults.asp?Family…

Parker, D.E., T.P. Legg, and C.K. Folland. 1992. A new daily Central England Temperature Series, 1772-1991. Int. J. Clim., 12: 317-342 www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcet/ [includes update to 2020]

Wilkinson, S. 2010. The changing (?) distribution of Tectura testudinalis.

Mollusc World 22: 10 – 12, Conch. Soc. GB & Ireland.

Zettler, M.L., Beermann, J., Dannheim, J. et al. 2018. An annotated checklist of macrozoobenthic species in German waters of the North and Baltic Seas. Helgol Mar Res 72 (5). doi.org/10.1186/s10152-018-0507-5 [scroll down and click ‘additional file 1’ for the list of taxa].